ALFRED HITCHCOCK – THE WORLD'S GREATEST DIRECTOR

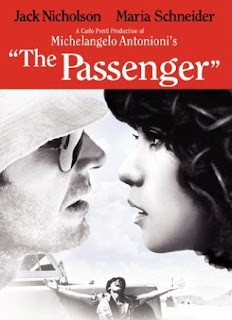

There's Bergman and there's Fellini; there's Antonioni and

there is Satyajit Ray. Today there is even Scorsese and it you want to push the

envelope you might even include the Coens or one of those Anderson boys, Paul

Thomas or Wes, (no relation). But name one who has gone into the lexicon, who

has produced their own adjective to describe, not just a way of working, not

even just a genre, but an artistic and psychological history of cinema that

spanned six decades. The only one I can think of is Alfred Hitchcock, the

greatest director of all time.

In an age when the movies meant to most people actors and

actresses Hitchcock was only one of two people behind the camera, (the other

was Walt Disney), known the world over. He was, of course, an entertainer

beginning his career in his native Britain before moving to America in 1940.

His first American film, "Rebecca" won the Oscar for Best Picture

though Hitchcock himself lost the best director prize to John Ford, the only

director to date to have won four directing Oscars while Hitchcock, remarkably,

never won a competitive Oscar, perhaps in the mistaken belief that entertainers

were not worthy of the big prizes

.

In Britain he had already earned the title 'The Master of

Suspense'. His much altered version of John Buchan's "The 39 Steps"

was the first of his masterpieces, a film in which one set piece followed

another. His cosier, "The Lady Vanishes", was the second of his

masterpieces and to some fans remains his best loved film. It was its

international success that launched his American career. "Rebecca"

was a gothic romance; in some respects it's an unlikely Hitchcock picture but

on closer inspection it's the film's dark psychology, (hints of lesbianism, the

memory of a dead woman who haunts the living), rather than the unlikely romance

at the centre which dominates. Here was a film that showed 'the master of

suspense' had a darker side to him that those earlier British films might have

suggested and although the forties were perhaps less fruitful for Hitchcock

than either the thirties or the fifties, (an unwise move to screwball comedy

with "Mr and Mrs Smith", the faux psychology of

"Spellbound", the turgid courtroom melodrama of "The Paradine

Case"), it was also the decade that saw him make two of his greatest

films, "Shadow of a Doubt" and "Notorious" as well as ten-minute take experiment of

"Rope", which daringly for 1948 hinted that two of its central

characters were in a homosexual relationship.

These films explored elements of Hitchcock's nature with a

depth that perhaps his earlier films only hinted at.

"Shadow of a Doubt" and

"Notorious" showed that both in family and romantic relationships

Hitchcock could be cruel, (we had already seen him blow up a boy in

"Sabotage"). Uncle Charlie, (a magnificent Joseph Cotton), was a

sexual predator who was prepared to murder his doting niece, (an equally superb

Theresa Wright), in "Shadow of a Doubt" while Cary Grant's secret

agent Devlin in "Notorious" was prepared to prostitute the woman he

loved, (a brilliant Ingrid Bergman).

At this point I should point out that while Hitchcock has

never been considered 'an actor's director', (his famous and misquoted 'actors

are cattle' remark),many performers have done some of their best work in his

films; Robert Donat in "The 39 Steps", Olivier, Fontaine and Judith

Anderson in "Rebecca", Fontaine again, and winning an Oscar, in

"Suspicion", Cotton and Wright as well as Patricia Collinge in

"Shadow of a Doubt", as mentioned Bergman and Grant in

"Notorious", Robert Walker in "Strangers on a Train", James

Stewart in "Rear Window", Milland, Grace Kelly and John Williams in

"Dial M for Murder", Stewart again as well as Kim Novak in

"Vertigo", Perkins and Janet Leigh in "Psycho", not to

mention the hugely underrated Tippi Hedren in both "The Birds" and

"Marnie". Could these performances really be the result of a man who

is said to have treated his actors like cattle?

In 1951 he made "Strangers on a Train" from the novel

by Patricia Highsmith, embarking on what was to be his greatest sustained

period. Highsmith was gay and, although never made explicit, so too was Robert

Walker's murderer in "Strangers on a Train". He picks up Farley

Granger's 'straight' tennis player on a train and tries to talk him into

committing a murder. Ironically, in real-life it was Granger who was gay. Here

was a thriller than was genuinely thrilling, psychologically dark and crammed

full of Hitchcock's best set-pieces. He followed it with perhaps his most

underrated great film, "I Confess", his most explicitly Catholic film

in which a priest is accused of murder because he can't reveal the secrets of

the confessional.

"Rear Window" came a year later. By now Hitchcock

wasn't just making 'conventional' murder yarns but movies that were prepared to

explore the very nature of cinema itself. Here was a film about looking, about

making audiences complicit in the crimes being committed on screen. Here was a

movie about voyeurism, (isn't just going to the movies a form of voyeurism), in

which James Stewart's photographer, (again a man who looks, who intrudes), laid

up in his apartment with a broken leg begins to spy on his neighbours, using

his camera's zoom-lens to get a better look. Stewart, Hitchcock and we, the

audience, never leave the apartment or the backyard where a good deal of the

'action' happens making this the director's most brilliant and formal use of

'space' as well as providing up with his greatest single set. In the course of

his spying Stewart thinks he has detected a murder which is where the suspense

kicks in. I have seen "Rear Window" many times and I never tire of it

even when I know everything that is going to happen.

In the same year he made what many consider a 'throwaway'

movie, again basically using a single set. Talked into making his screen

version of Frederick Knott's play "Dial M for Murder" in 3D the film

was released mostly 'flat'. To many it's minor Hitchcock but I love the film;

its suspense, its comedy, its bravura set-pieces, (who else could have gotten

so much out of one room), and the brilliant performances of Ray Milland, Grace

Kelly, (the quintessential Hitchcock heroine), John Williams and, as the

potential murderer who ends up the victim, Anthony Dawson. Only the bland

Robert Cummings lets the side down.

If his next two films, ("To Catch a Thief" and

"The Trouble with Harry"), are minor Hitchcock's they are at least

very pleasurable divertissements, remembering that minor Hitchcock is always so

much better than the best of lesser directors, leading, in 1956, to "The

Wrong Man", an almost documentary-like account of a miscarriage of

justice. This was definitely not the kind of film we had been used to seeing

from Hitchcock up to that point. For starters, it was based on the true story

of "Manny" Balestrero, mistakenly accused of a robbery and imprisoned

for a crime he didn't commit, leading to the breakdown of his marriage and the

institutionalization of his wife. It was only a thriller in that we hang on to

see it the truth will come out. Hitchcock shot it on locations, adding an

authenticity it might otherwise not have had, the main focus of his attention

being Manny's breakdown and that of the family unit. At the time both critics

and audiences didn't quite know what to make of the film; now it is regarded as

one of the best things he has ever done.

In the same year Hitchcock remade one of his earlier films, “The

Man Who Knew Too Much”, altering both the locations and a good deal of the

plot. The original is beloved my purists who believe we should never tamper

with anything and if it ain’t broke it don’t need fixing. I prefer the remake,

(it’s both funnier and more suspenseful). It was also around this time that he

moved to television with a long-running series of, at first thirty minute and

then sixty minute, shows dealing with crime in one form or another. He seldom

directed personally but his name and his introductions ensured their success.

And then in 1958 he made “Vertigo”, the first of five enduring classics in a

row.

When it came out “Vertigo” was not a success, particularly

amongst critics who found the lack of suspense and the emphasis on the

psychology of its central character a tad on the dull side. However, in the

last Sight and Sound poll, “Vertigo” overtook “Citizen Kane” as the greatest

film ever made. With “Vertigo” he continued breaking the rules, (with the

underrated “Stagefright” a few years earlier, he gave us a flashback that was a

lie). With “Vertigo” he let us into ‘whodunit’ about three quarters of the way

through the movie. The film was a mystery but not necessarily a murder mystery.

Was it also a ghost story? And could it really be about necrophilia? Did James

Stewart’s character Scottie really want to mould Madeleine into the woman he

believed was dead?

It's a film that repays repeated viewings; like all great

psychological dramas it’s the play between the two main characters that grips.

Our interest isn’t primarily on what has happened as on what is going on inside

the character’s heads. Stewart, arguably the greatest actor in the history of

the movies, is magnificent here and Kim Novak, never the most expressive of

actresses, is perfectly cast as the woman he finds, loses and finds again, (her

very blankness allows us to read so much into her character). It’s not my own

personal favourite Hitchcock but I certainly won’t deny its greatness.

His next film, “North By Northwest” may be his most popular

and was seen by critics as a return to form. It was an old-fashioned comedy

thriller harking back to the spy movies of the thirties and forties. You could

say he rehashes many of his earlier set-pieces but on a much larger scale and

in the crop-dusting sequence, he gave us one of cinema’s most iconic scenes.

Like all great comedy-thrillers it too repays repeated viewings and, of course,

it helped that his hero was once again played by the great Cary Grant, way too

old for the part, (Jessie Royce Landis, who played his mother, was only 8 years

older than Grant), but perfect nevertheless. Indeed, this was just the kind of

film the studios would have wanted him to repeat, a sure-fire commercial

success. Instead he made “Psycho”, an outright horror film shot in black and

white. It could have failed horribly, too but thanks to Hitchcock’s own

brilliant publicity it was his greatest success and, I think, his greatest

masterpiece.

Innovative in so many ways, “Psycho” was unlike anything he

had done before. It begins like a straightforward tale of a robbery with a

leading lady, (the superb Janet Leigh), who is virtually never off the screen

thus making it very easy for the audience to identify with her. Then midway

through the film Hitchcock pulls the plug on us quite literally as Leigh’s

Marion Crane is very brutally stabbed to death in the shower, (in what may be

the most sequence in the movies), and the film shifts gear once again to become

a tale of murder most foul. It would appear the killer is also a woman, the

mother of the films newly introduced ‘hero’, Norman Bates, (Anthony Perkins in

a career-defining role), but this is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s

another murder before Hitchcock tidies everything up in a brilliant and daring

bit of cod-psychology in which a psychiatrist ‘explains’ the plot of the film

we have just watched. Even knowing the resolution here is a film we can watch

over and over again and a film I think I can reliably call Hitchcock’s

greatest.

Three years passed before Hitchcock made another film, this

time delving further into the horror genre with his screen version of Daphne Du

Maurier’s short story “The Birds”. Technically the film is a marvel but it is

so much more than that. He never explains why the birds behave the way they do,

rather he builds up set-piece after set-piece of bird attacks and ‘action’

while allowing us time to ponder why the humans in the picture behave as they

do. Some critics were dismissive of the film at the time as a piece of clever ‘junk’;

it is now rightly regarded as a classic.

For his next film Hitchcock was reunited with his star of “The

Birds”, Tippi Hedren, (he had wanted Grace Kelly but her husband refused to let

her make the picture). After the technical flourishes of “Psycho” and “The

Birds”, “Marnie” was a distinct throwback to his set-bound psychological

thrillers of the forties. It was about a frigid kleptomaniac blackmailed into

marriage by the man who was stealing from and who probably rapes her on their

wedding night, (discreetly done, by the way). Critics, for the most part, hated

it but again, like “Vertigo”, it has been reassessed and is now quite highly

thought of and, like “Psycho”, it ends on a piece of cod-psychology in which

the heroine’s actions are also ‘explained’.

By now Hitchcock was 65 and was to make only four more

feature films. Though they had their good points, both “Torn Curtain” and “Topaz”

are mostly forgotten. In 1972 he went back to Britain where he filmed Arthur Le

Bern’s novel ‘Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square” as “Frenzy”. After

his previous two films this was seen as a real return to form. It was also seen

as perhaps his most vicious film, certainly since “Psycho”. Its villain was a

sexual psychopath and by now Hitchcock was getting bolder in showing his

murders. “Frenzy” turned out to be his penultimate film. For his final film, “Family

Plot”, he went back to California. This was certainly his ‘lightest’ film since

the fifties, with his con-artists and thieves seldom reverting to violence.

Again, critics largely dismissed it but its pleasures were that of a good

script and four excellent performances from Bruce Dern, Karen Black, William

Devane and Barbara Harris and it certainly wasn’t the failure that many

suggested and turned out to be a better end to his career than many might have

feared

In 1967 he was awarded the Irving G Thalberg Memorial Award, the only Oscar he was to personally receive. He had his failures, certainly, but how many directors made as many masterpieces in a career than spanned six decades. How many directors entertained us and probed into the darkest reaches of our psychics as Hitchcock, and often in the same moment. He story-boarded all his films but he cherished good writers. Actors, he is reputed to have said, should be treated like cattle and yet he drew many great performances from his players and he knew more about technique than any director working at the same time. When you watched a Hitchcock film you knew you were watching a Hitchcock film; no-one else made films like him and we will never see his like again.

Third World poverty is a subject the

cinema seems unwilling to tackle, perhaps understandably so since the

movies are fundamentally a commercial enterprise and 'entertainment' is

the name of the game. When 'western' cinema tackles the subject, (and I

am thinking here of Hollywood cinema), it tends to romanticise it or make it the subject of a thriller so it's often left to 'native' cinema to deal with their own issues and a lot of the time, when they do, the subject is turned around and treated as an 'action' flic or simply ignored altogether. "La Soledad" is mercifully, and thankfully, the exception.

Third World poverty is a subject the

cinema seems unwilling to tackle, perhaps understandably so since the

movies are fundamentally a commercial enterprise and 'entertainment' is

the name of the game. When 'western' cinema tackles the subject, (and I

am thinking here of Hollywood cinema), it tends to romanticise it or make it the subject of a thriller so it's often left to 'native' cinema to deal with their own issues and a lot of the time, when they do, the subject is turned around and treated as an 'action' flic or simply ignored altogether. "La Soledad" is mercifully, and thankfully, the exception. Jorge Thielen Armand's film hails from Venezuela where

poverty and crime are debilitating issues. In a society ruled by

violence Negro and his family have virtually nothing, living on the edge

and with the likelihood of being thrown out of the crumbling mansion

where they are virtual squatters. There is no melodrama in the telling

of their tale and little drama either. Armand simply observes his

characters as they struggle from one day to the next. This could be a

documentary and his cast, all playing themselves, respond with

extraordinarily naturalistic 'performances'. The tragedy lies in our

knowledge that for many people in Venezuela life is unlikely to get any

better than it is shown here. 'Action', for want of a better word, when

it happens does so off-screen and yet, never for a moment, could you

describe this film as boring; the potential for violence never actually

seen is never far from the surface. Let's hope this extraordinary film

finds the audience it deserves.

Jorge Thielen Armand's film hails from Venezuela where

poverty and crime are debilitating issues. In a society ruled by

violence Negro and his family have virtually nothing, living on the edge

and with the likelihood of being thrown out of the crumbling mansion

where they are virtual squatters. There is no melodrama in the telling

of their tale and little drama either. Armand simply observes his

characters as they struggle from one day to the next. This could be a

documentary and his cast, all playing themselves, respond with

extraordinarily naturalistic 'performances'. The tragedy lies in our

knowledge that for many people in Venezuela life is unlikely to get any

better than it is shown here. 'Action', for want of a better word, when

it happens does so off-screen and yet, never for a moment, could you

describe this film as boring; the potential for violence never actually

seen is never far from the surface. Let's hope this extraordinary film

finds the audience it deserves.